Shared by Maya Yadid

For families who continue the centuries old tradition of preparing overnight Shabbat stews like Ashkenazi cholent, Sephardi hamin, Moroccan dafina, or Iraqi t’bit, it’s common to have one recipe that’s their own. It’s a dish that expresses where the family comes from, often evolving as generations migrate, each cook adding their own touch.

In artist Maya Yadid’s family, they count three hamin recipes as part of their tradition. There’s chicken with cracked wheat and freshly ground cumin, and a more modern “macaroni hamin” comprised of chicken and noodles in a tomato sauce that originated in Jerusalem, where her mother’s family has lived for more than 130 years. Finally, there’s the prized falda hamin or “festive hamin.” It’s a labor of love that’s loaded with hunks of beef, white beans, steak stuffed with rice (the falda), bread patties called kuklas, and eggs that you can sneak out of the pot in the morning for breakfast. You don’t need to add many spices, Maya explains, “The time is what matters — that's what does the work. That’s the real spice.”

The recipe comes from Maya’s late grandmother Leah, who was born in Jerusalem in 1929, and Leah’s mother Shulamit, who emigrated in 1895 by donkey from Urfa in southeastern Turkey. Located just north of the border with Syria, the area was home to Sephardi Jews, Armenians, Kurds, and Turks, creating an intersection of diverse cultures and flavors. “That’s why the food there is so special,” Maya adds. It’s also where the cracked wheat hamin comes from. Generations ago, the festive hamin was made with stuffed kishke (intestine) and kirshe (stomach), but they were labor intensive to prepare and the cuts became harder to find, so the recipe evolved. The bread patties were likely introduced during the Tzena, a period of austerity in the early days of Israel.

Maya remembers the pots of festive hamin prepared by Leah warmly. It wasn’t just the recipe that made the pot special. Her grandmother had a quality to her cooking that’s hard to capture, an instinctive touch. “She was a passionate cook. And had a really special hand, ” Maya says.

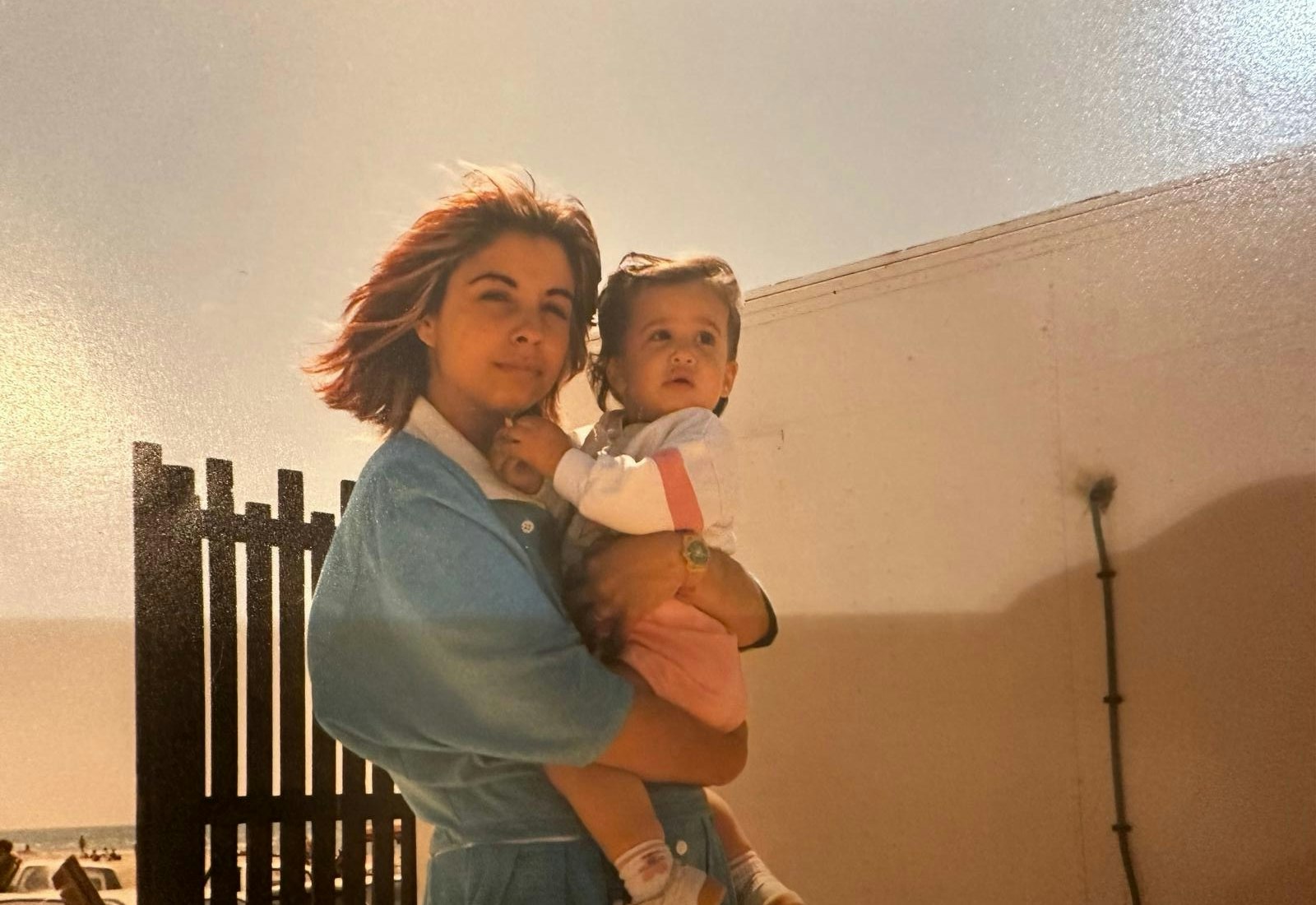

Leah passed along her recipes, including the festive hamin to Irit, her daughter-in-law, whose family is also from Urfa, as well as Yemen. This is where Maya says her family history merges — or, perhaps reconnects. Thinking aloud about both sides of her family generations ago in Urfa, she says: “They may have been neighbors, they may have been family — or maybe not, but it was a small community.”

As talented a cook as Leah was, Irit has improved on the recipes, Maya shares. She also brings her Yemenite heritage to her cooking, serving the hamin with zippy schug, an herby hot sauce from her other side of the family to balance the richness of the pot.

Maya has inherited some of Leah’s recipes including her stuffed grape leaves, which she makes with vines that grow wild around her home in upstate New York. But, cooking Leah’s recipes doesn’t always come easily to her. As she prepared Leah’s cheese sambusak and pumpkin kubbeh soup for her 2020 art piece “Tribute to Leah,” Maya worried about every measurement. Her brother, who is a chef, finally told her: “You gotta be Leah to make this food. Just move in the kitchen the way she moved, and you'll get it right,” she recalls. “That's something that leads me whenever I cook.”

But for now, Irit is the keeper of the festive hamin. When she visits Maya and her family she makes it if the moment is right. Maya still prefers to leave the recipe to the “pros” as she puts it. “I don’t feel like it’s exactly my territory yet.”