Shared by Samantha Ellis

Samantha Ellis is the author of “Always Carry Salt: a Memoir of Preserving Language and Culture,” as well as other books including “How to be a Heroine,” and plays including “How to Date a Feminist.” She lives in London with her son. Here, she shares her story in her own words.

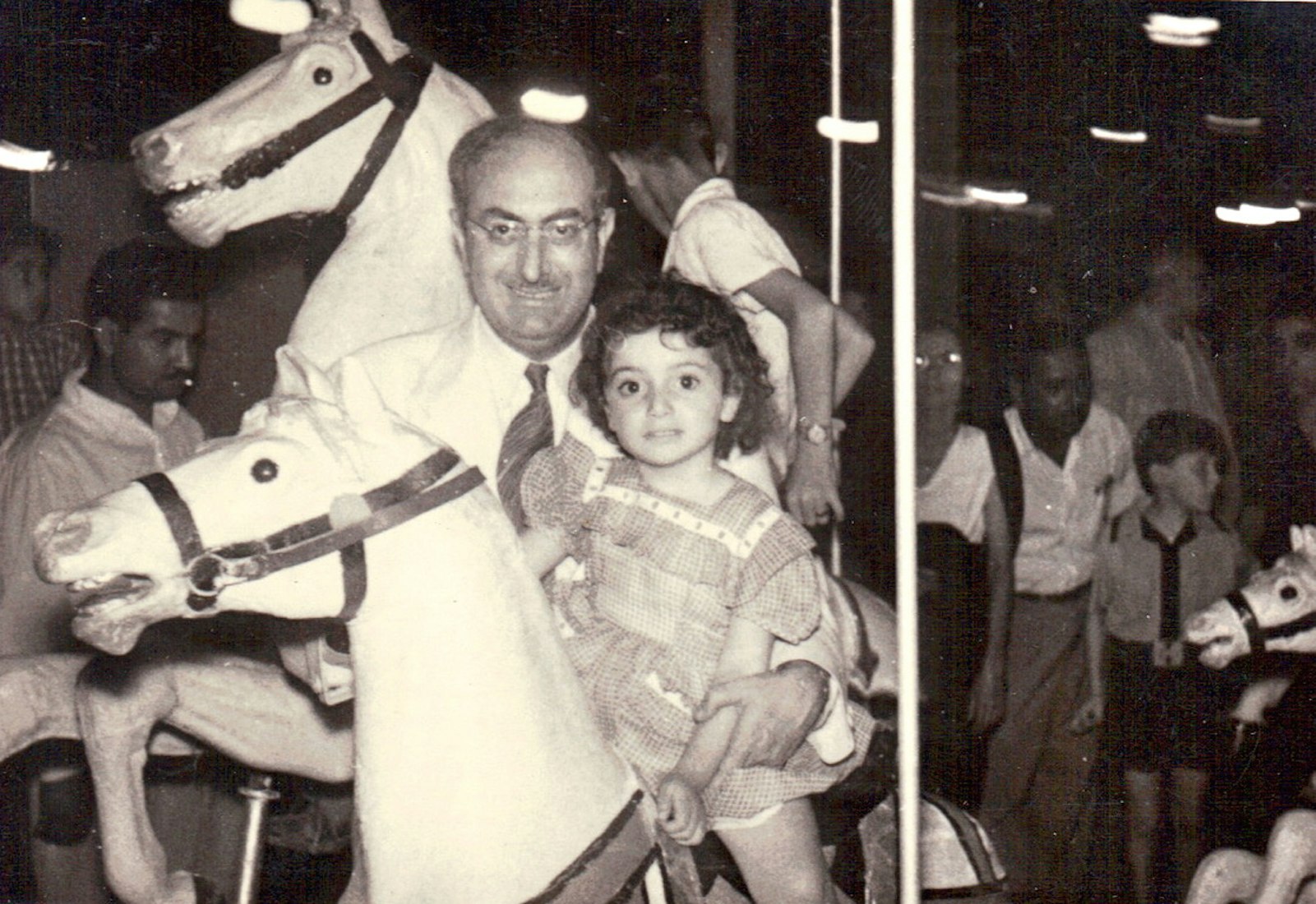

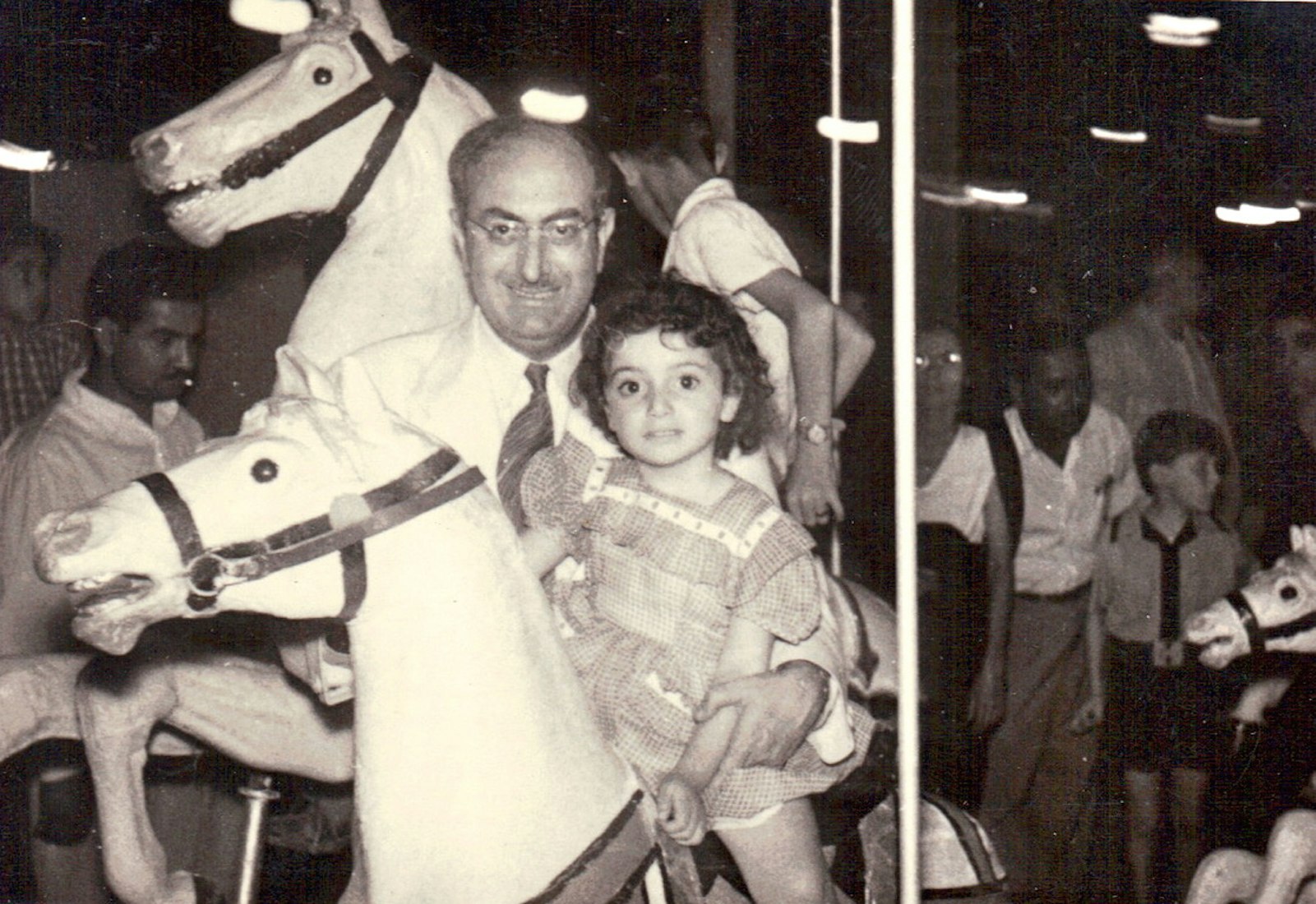

If I could go back in time, I’d like to be three, sitting under the Formica table at my grandmother’s house in suburban London in 1978, pulling the stalks off parsley for tabbouleh, listening to the grown-ups gossip, scarlet painted fingers in motion, gold bangles tinkling, the air thick with cigarette smoke and Shalimar perfume.

My parents were both born in Baghdad where, in the 1940s, the city was one-third Jewish. My father left in 1951 in the mass airlift of around 125,000 Jews to Israel. My mother's family left much later, in 1971, having experienced horrific persecution in the 1960s. Today, there are reportedly only three Jews left in Iraq.

When I was little, Iraqi Jewish food was all I wanted to eat. For school my mother made me wonderful packed lunches of puffy pita stuffed with t’beet eggs (cooked overnight on Shabbat with chicken so they were infused with its flavor), hummus, fried slices of eggplant, salad, and of course the iconic Jewish Iraqi mango pickle amba. But when friends mocked me, like a coward I switched to sliced bread and cream cheese.

When I left for university, my mother bought me a rice cooker. It could have been a chance to reconnect but instead, away from my community, imposter syndrome kicked in. Who was I to cook Iraqi Jewish food? What if I got it wrong? Born in London, I felt I wasn’t really Iraqi. I was a tourist, and a tourist can’t also be a tour guide. I made friends who weren’t Iraqi or Jewish, and I loved them but it also felt strange that I didn’t call their mothers “auntie” and that their grandmothers had never pinched my cheeks with surprising force.

I graduated feeling less Iraqi Jewish than ever, disconnected and unsure.

It was only when I started cooking Iraqi Jewish food that I began feeling more at home, more like me. I don’t know what prompted me to start. A kind of inchoate longing for home, maybe — or perhaps it was that suddenly everyone was cooking Middle Eastern food.

The first thing I cooked was kichree, Iraqi Jewish comfort food: rice with red lentils, turmeric, cumin, melting onions, butter, and halloumi, which we eat with yogurt spooned over the top. If there are leftovers, I love them with an egg fried over the top.

For my friends, I cooked little meatballs called ras asfour, which literally means “sparrow heads” because they are about that size, served in a rich red beetroot stew. I made dense, cataclysmically cheesy omelettes called ajjat b’jeben (cheese storm), and ingriyi, fried eggplant, layered with fried lamb or beef and tomato, and simmered with turmeric, lemon juice, and date syrup. I even had a go at t’beet.

It was more than just the food. It was bringing people together. It was making a lot; my mother taught me to make so much that when everyone has finished eating, the table looks as full as if they haven't started.

Still, something was missing. I cooked anxiously, phone in hand, checking with my mother that I wasn’t getting it “wrong.” I became a stickler for authenticity, railing against fusion food, not admitting it was because I was scared I was a fusion person, neither one thing nor another; too English with my family, too Iraqi Jewish everywhere else.

Things only started to shift when, researching my memoir “Always Carry Salt,” I was stunned to realize that amba was a fusion food. The story (or perhaps it is a legend) goes that it was invented by Iraqi Jews who had left Iraq for India — perhaps even by Siegfried Sassoon’s great-grandfather David Sassoon, who supposedly fell in love with Indian mangoes and wanted to share them with his friends back home. When he realized they wouldn’t survive the journey, he had the bright idea of pickling them. It probably wasn’t David Sassoon, but amba almost certainly came from homesick Iraqi Jews encountering new flavors.

At first this depressed me. If even amba was fusion food, how could anything be truly authentic?

Then I realized I was being absurd. Of course amba is authentic to Iraqi Jews wherever it was invented. It’s our dayglo sticky essence, our sour-sharp heart. I read food writer Soleil Ho on trying to “stretch” familiar dishes without losing their soul, and wanted to stretch too, to feel freer in my cooking — and even in my life. I wanted to be like bold cooks I admired such as Joanna Hu and Rosheen Kaul whose book is called “Chinese-ish” or Ravinder Bhogal who gave her book “Jikoni” the subtitle “Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen.” The pressure to feel authentic felt like one I would be happy to let go of.

One cold evening in London I had the urge to cook something vivid, warm, and soothing: it had to be saluna. The joy of the baked fish dish is its sauce, which is hamedh-helu (sweet and sour), the Iraqi flavor. It’s often said it’s because of our sweet and sour history in Iraq, but not by me because not everything has to be a metaphor. I had made it before, but I didn’t feel secure in my recipe somehow. I was still nervous.

In Daisy Iny’s tragically out-of-print cookbook, “The Best of Baghdad Cooking,” she wrote that she made the sweet and sour with lemon juice and sugar but noted that in Iraq, they usually replaced the sugar with date syrup. I asked my family Whatsapp group how they made it and suddenly my phone was lighting up with messages from my cousins and aunt. For the sour element, they suggested pomegranate molasses, tamarind, or pulverised dried lime as Jewish culinary scholar Claudia Roden notes. For the sweet it could be date syrup or sugar — none of us was keen on honey, and when I said I’d found one recipe using maple syrup there was uproar.

As our conversation got more animated — even raucous — I suddenly felt like I’d gone back in time. We might not be in Baghdad, or even under that table in London years ago, but we were all connected, savouring, disagreeing, laughing, remembering recipes, honouring traditions, and adventuring joyously with them too.